‘My children ask me when am I coming home’: stranded seafarers share their frustrations

Hundreds of thousands of seafarers are finding themselves stranded at sea, sometimes for over a year, and with no end in sight, as a result of COVID-19 travel restrictions. The uncertainty and long spells away from home are taking a heavy mental toll.

“I am tired, exhausted and hopeless. I have been at sea for 12 months already. And I don’t know when I can see my kids and family. It’s very frustrating.”

Raphael (not his real name) has no idea how long he will be stuck on his ship. A 33 year old seafarer from the Philippines, with two children, he was scheduled to fly home in April, but the pandemic put paid to his plans: airports have been closed, and his company decided not to relieve him, and eight other colleagues, some of whom have spent up to 14 months onboard.

“This is the fourth time my home leave has been cancelled. I don’t know what’s going on. We deliver the cargo and the goods, but they close the borders for us.”

Because of the uncertainty, Raphael says, the atmosphere on the ship is tense, and he fears that there will be an impact on safety, because of the fragile mental health of the crew: “our minds are in different worlds”, he says. “It’s like walking on thin air.”

’All we want is to come home’

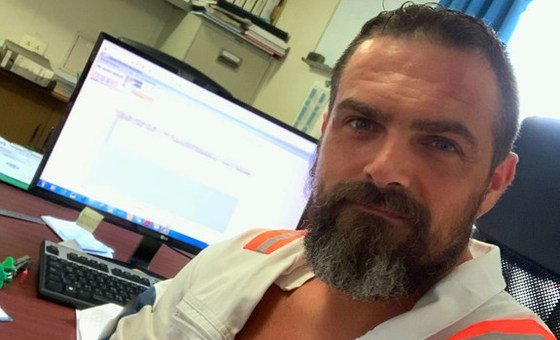

Some 90 per cent of global trade takes place via maritime transport, thanks to the work of around two million seafarers. Like Raphael, Matt, an English Chief Engineer onboard a boat that sails mainly in the Middle East and Asia, feels that the crucial contribution made by seafarers, who ensure that the transportation of key goods continues unimpeded during the pandemic, should be valued more highly.

“I would say that, as seafarers, we have more than played our part during this pandemic. We have kept countries supplied with everything they need, including PPE (personal protective equipment) and medical supplies, oil and gas to keep power stations running, and food and water. All we want in return is to be able to come home and rest”.

Matt’s contract is well overdue, and most of his crew members are in a similar situation: “The officers have 10-week rotation contracts, but most of us have now been onboard for 6 months or more. It is even worse for the crew: they’re on nine-month contracts, but I have one crewman who has been onboard for 15 months.

Waiting at home for Matt are two children, aged eight and 12, and the separation is proving difficult for all members of his family.

“I’ve done long contracts before, but this is different. It has a psychological effect, as there is no end in sight. It affects family life a lot more. My children are always asking when am I coming home. It’s difficult to explain to them.”

As time has gone on, Matt and the crew have gone through a range of emotions, and the mental health burden is growing.

“I think we’ve been through all the emotions. A lot of anger in the beginning as we had to watch all the borders close. We understood the health risk, and we could understand why it was happening. We tried to remain hopeful, but as time has passed it seems like little has changed. We are hanging in here, but we are tired and mentally fatigued.”

Isolation on the high seas

Wagner Brandt is the Head of the Transport and Maritime Unit at The International Labour Organization (ILO). As a former Naval Officer, he recognizes the challenges experienced by stranded crew members.

“The sea can be tough. When the weather’s bad it’s pretty awful. Also, those onboard are living for several months in the same place that they’re working. These days the industry is highly efficient, so a container ship can be unloaded and loaded in a few hours. Ports are now some distance from town centres and, in the case of oil tankers, you might be discharging or taking on oil, at an off-shore facility. So, seafarers have fewer opportunities to disembark than they did in the past. It can be very isolating”

Thanks in part to the work of the ILO, conditions for seafarers have steadily improved over the years: “in 2006, we set up the Maritime Labour Convention, often referred to as the seafarers bill of rights. This sets out the minimum working conditions for all seafarers, including provisions such as the minimum hours of rest, occupational safety and health, and states that no seafarers should be at sea for more than 11 months. Today, the vast majority of the ships in the world are flying the flag of States that have ratified this convention.”

“There are still problems, of course, such as low pay, seafarers forced to work long hours, or abuse, but this is why we have international instruments, to set minimum work standards, and see that they are enforced.”

These conventions have been sorely tested by the current pandemic, however. Seafarers may have to travel thousands of kilometres to reach their ships, or return home. Since the pandemic, commercial flights have been significantly reduced, borders have been closed, and it has become more difficult to obtain visas or travel permits through certain transit countries.

The unheralded contribution of the seafarer

To help Matt, Raphael, and the more than 200,000 seafarers struggling to cope with a seemingly endless stint on the seas, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), set up the Seafarer Crisis Action Team (SCAT), in partnership with the ILO, the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) and the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). SCAT has successfully intervened in several individual cases, finding solutions that will allow seafarers to go home.

The IMO is pushing for all governments to classify seafarers and other marine personnel as “essential workers” which would make it easier for safe crew changeovers to take place. Following a ministerial summit in July, held in the UK, 13 countries committed to recognizing seafarers as key workers, and facilitating crew changes.

The cause has also been taken up at the highest levels of the UN, with Secretary-General António Guterres expressing concern about a growing ocean-bound humanitarian and safety crisis, and praising the “unheralded contribution” of seafarers to the global economy, and bringing life-saving supplies to civilians trapped in conflict zones, such as Yemen.

For Matt, the change can’t come soon enough: “We need the support of world governments to allow us to transit through their countries without restrictions. Time frames for visas need to be reduced or scrapped all together.

This needs to happen now. The delay is going to have a detrimental effect to the maritime industry. There has been more than enough time for talking: now we need to see real action.”